JavaScript has a liberal array of techniques for constructing objects. Although object oriented style programming can be simulated in Javascript (which is prototypical in nature), it can get a little unwieldy.

Pseudoclassical OO

The following code is in the style referred to as pseudoclassical by Douglas Crockford in Javascript: The Good Parts:

var Person = function(name, empathy) {

this.name = name;

this.empathy = empathy || 0;

};

Person.prototype.get_name = function() {

return this.name;

};

Person.prototype.get_empathy = function() {

return this.empathy;

};

Person.prototype.change_empathy = function(amount) {

this.empathy = this.empathy + amount;

return this.empathy;

};

Person.prototype.status = function() {

return this.get_name() + " has " + this.get_empathy() + " empathy";

};

var Player = function(name, empathy) {

this.name = name;

this.empathy = empathy || 0;

};

Player.prototype = new Person();

var Mob = function(name, empathy) {

this.name = name;

this.empathy = empathy || 0;

};

Mob.prototype = new Person();

And we can use the ‘classes’ like so:

var player = new Player("Ada", 100);

console.log(player.status()); // 'Ada has 100 empathy'

var mob = new Mob("Bob", -10);

console.log(mob.status()); // 'Bob has -10 empathy'

mob.change_empathy(2);

console.log(mob.status()); // 'Bob has -8 empathy'

There are a few things to note here:

- There are no private fields or methods, it’s not feasible to add them

- There is duplication in constructors that lie in an inheritance chain (i.e. where an object’s prototype is set to another object)

- It’s horribly verbose (a matter of personal taste however)

- Due to the lack of private fields, you can’t have a method called

name()that returns a field calledname- one will overwrite the other in this style

The limits of inheritance

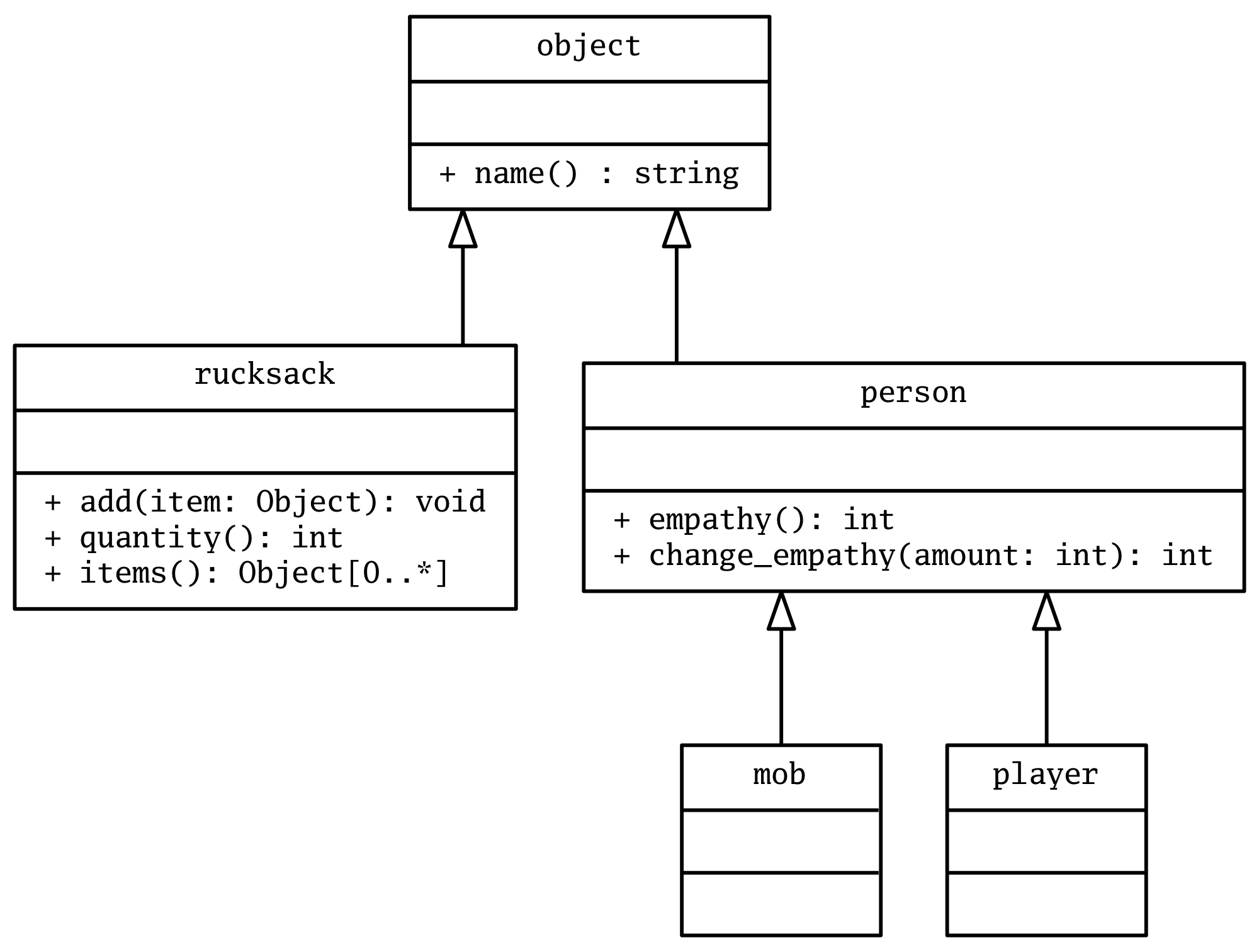

Even ignoring these issues (and there are other ways to create objects that work around this limitation), object oriented inheritance is not the most flexible way to design software. For many domains of problems, composition or augmentation trumps inheritance. Let’s examine a motivating example. In the following class diagram we have some domain objects for a game. Players and Mobs are Person(s), Person(s) and Rucksacks are Objects. All is well with this view of the world, no code is duplicated between objects and it all works as intended.

Here are some unit tests of these objects to illustrate their functionality:

var JS = require("jstest"),

components = require("../lib/components");

JS.Test.describe("components", function() {

this.before(function() {

this.rucksack = components.rucksack({name: "Bag of Holding"});

this.another_rucksack = components.rucksack({name: "Bigger bag"});

this.spell = components.spell({name: "Potion of empathy"});

});

this.describe("container", function() {

this.it("can contain other containers", function() {

this.rucksack.add(this.spell);

this.another_rucksack.add(this.rucksack);

this.assertEqual(1, this.another_rucksack.quantity());

this.assertEqual("Bag of Holding",

this.another_rucksack.items()[0].name());

});

this.it("can contain other objects", function() {

this.rucksack.add(this.spell);

this.assertEqual(1, this.rucksack.quantity());

this.assertEqual("Potion of empathy",

this.rucksack.items()[0].name());

});

});

});

Now say we want to extend our player objects to have an inventory (or

container). We could approach this in a number of ways but

inheritance is not one of them. We already have rucksack and

person inheriting from object so we can’t just create container

as a superclass of those. We need a way to extend both those objects

and extract the container-related behaviour and state so we don’t

have code duplication. In Ruby, we might create container as a

Module and include it in our classes.

The method pattern in JS allows us to do something quite similar, but first, let’s write a failing test:

this.describe("player", function() {

this.it("has an inventory", function() {

this.assertEqual(0, this.player.quantity());

this.player.add(this.spell);

this.assertEqual(1, this.player.quantity());

this.assertEqual("Potion of empathy", this.player.items()[0].name());

});

});

The Module Pattern

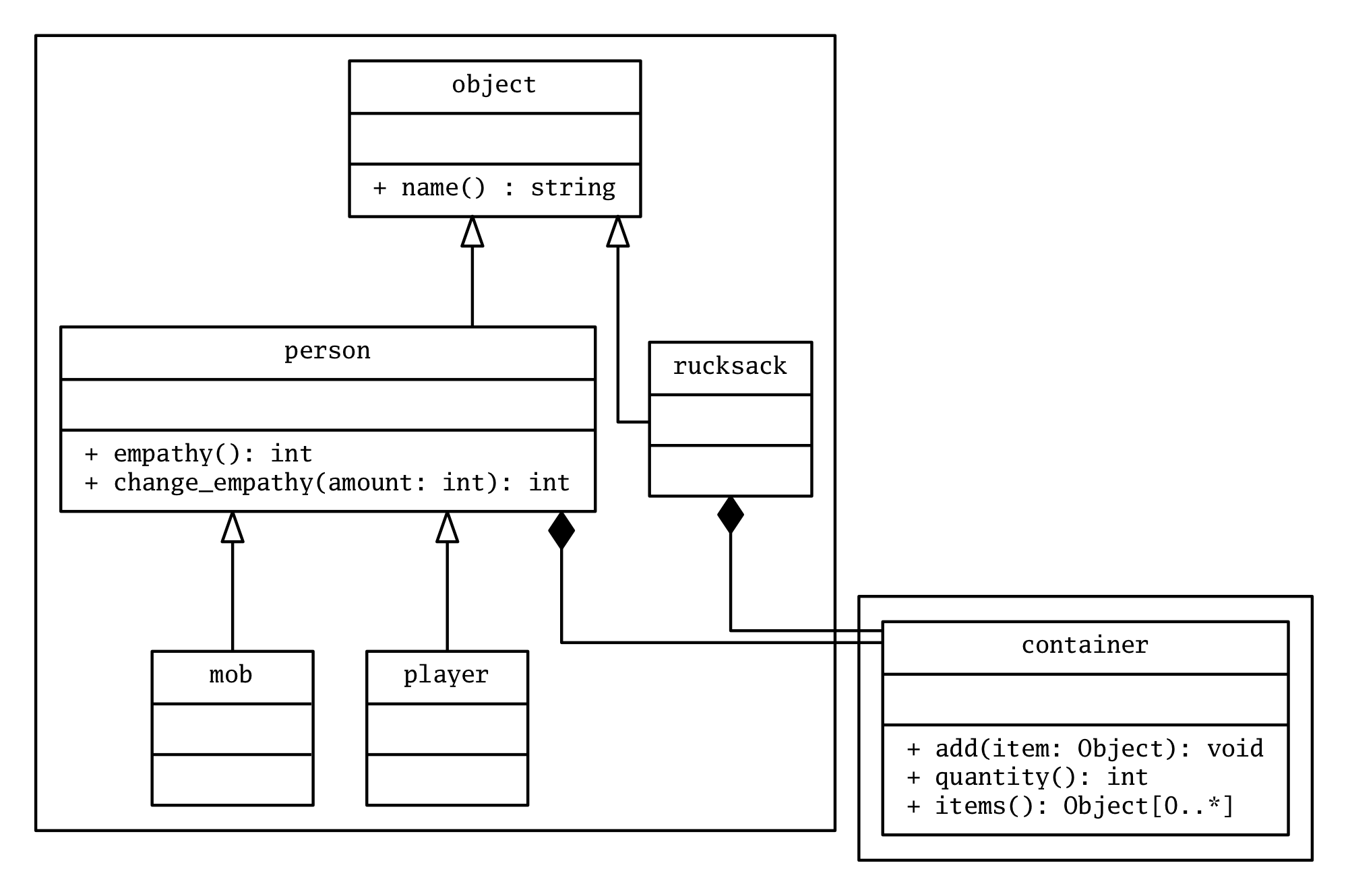

Now we can go ahead and examine how to construct the relationship

between objects that we need. This diagram approximates the idea (I’m

not exactly clear what options to pass GraphViz to make the

container obviously indicate it is included as a module):

The basic ‘shape’ of an object using ‘functional composition’ looks like the following:

var object = function(spec) {

var that = {};

that.name = function() {

return spec.name;

};

return that;

};

The spec argument is the object to be augmented (sometimes that’s as

simple as being the parent object). The that object which gets

returned constitutes the public interface that this object returns.

Because spec is passed in and that is returned, this object

constructor is a base class.

The container constructor function looks like this:

var container = function(that) {

var inventory = [];

that.add = function(item) {

inventory.push(item);

};

that.quantity = function() {

return inventory.length;

};

that.items = function() {

return inventory;

};

return that;

};

Unlike the previous example, container exists to decorate the

provided object with more functionality. If you needed to provide

defaults for this object specifically, you can pass a spec argument

in also but it wasn’t necessary here. Crucially, the inventory

variable is lexically scoped to the container constructor, meaning

no code gets access to it except that inside the container

constructor. This is in contrast to Modules in Ruby where

everything, fields and all, gets included into a Class and becomes

part of that class.

The person object is a little different:

var person = function(spec) {

var that = container(object(spec)),

empathy = spec.empathy || 0;

that.change_empathy = function(amount) {

empathy = empathy + amount;

};

that.empathy = function() {

return empathy;

};

return that;

};

We’re back to using a spec argument here so that we can instantiate

a person with some default amount of empathy. The that = container(object(spec)) stands in for traditional object inheritance.

After we’ve created the container object and wired it up to person

and rucksack, the code for concrete objects in our toy example looks

like this:

module.exports.rucksack = function(spec) {

var that = container(object(spec));

return that;

};

module.exports.mob = function(spec) {

var that = person(spec);

return that;

};

module.exports.player = function(spec) {

var that = person(spec);

return that;

};

module.exports.spell = function(spec) {

var that = object(spec);

that.affect = function(obj) {

if (that.inRange(obj)) {

obj.change_empathy(1);

}

};

return that;

};

Although the diagram above implies a strict inheritance hierarchy,

that is not necessarily the case. The difference between object and

container is subtle, with object hiding the spec object and

returning a new object (just as person and rucksack do), whereas

container just adds methods to an object.

One last thing! It might be apparent, but it’s worth calling out the

other advantage this gives us: dynamic runtime extensions. If you want

the spell object to be able to contain items, you could do so at any

stage, running:

var my_spell = spell({name: "Confusing potion"});

// my_spell doesn't have an inventory

container(my_spell);

console.log(my_spell.quantity()); // '0'

This code modifies the my_spell variable, but no other variables

that use the spell constructor function. This could be useful in

games where items can interact, giving each other different

functionality (e.g. imagine a potion that allows bookcases to float or

drinking a flying potion adds the flying component to a player). In

those cases, there’s no need for complex if/else/switch-style

programming, just augment the object with the desired module

and that’s it!