On the weekend of 6th December 2014, I participated in Ludum Dare 31. The theme was “Entire Game on One Screen”. I didn’t finish my game and didn’t hand anything in. This is the 3rd(?) time I’ve started but not finished a Ludum Dare game in recent years. The first time I participated in Ludum Dare, I completed a game and handed it in for the competition (48 hours), so I’m curious as to what has been holding me back since then.

Lack of planning

It was only after Ludum Dare was completed and I filled in a Trello board with the tasks necessary to complete my game that I realised the immensity of the project. I was reading Amy Hoy’s new book Just Fucking Ship and it emphasises working backwards from a goal to a set of tasks that need to be done. Hoy also advocates Mise en place style of working, which I’ve never identified as a thing before but it’s obvious in hindsight. Ludum Dare advice usually contains something about starting on paper, getting all the high-level details worked out before diving into code and that’s absolutely right. The other massive advantage of having a todo list (e.g. in Trello) is that it’s super easy to order the list of things in terms of what needs to be done and what is optional. Does it matter that the resolution is fixed at 800x600? Nope. But I’ve totally sunk hours/days into coding around the idea I need to have a scalable interface on the web for my games (and it’s always really painful).

Case in point - this Ludum Dare, I decided to use Elm, which was entirely new to me. The conventional wisdom has it that one should never learn tools while participating in Ludum Dare, just use whatever you have at hand (i.e. programming languages/IDEs/libraries etc. that you have used extensively before). I only make games during Ludum Dare though and I’ve never reached a level of proficiency with gamedev that I feel leaves me with a default technology choice, so I used a new thing. However, this time round, using Elm, the web game ends up getting drawn using the 2D canvas and image elements positioned on top of it basically. You can’t control a lot of how Elm does any of this and there was a minor wrinkle - there’s no way to use CSS’s image-rendering option to optimise for pixel art (crisp-edges is what you want - which is essentially nearest-neighbour scaling up/down). The result is you get blurry pixel art in your games and this sucks. It’s not at all a blocking problem for Ludum Dare games though and I feel silly for spending any more than 5 minutes on it.

Overly ambitious game design

I’m not a regular gamedev, this is something I do very occasionally. I’m a software engineer and therefore I completely and wildly underestimate the complexity and difficulty of programming tasks. Not to mention my total lack of ability to gauge time requirements. In the world of work, many of us software engineers avoid the near-impossible task of time estimation by using Agile-based practice and estimating complexity instead. It’s entirely based on teamwork and iteration of process and makes no sense for an individual working towards a goal on a deadline.

Aside: within the confines of Agile processes and teams, individuals can and do use more “traditional” time estimation and tracking tools to live up to their own expectations of themselves, so we do think “this will probably take half a day” but the discipline of working in an Agile team is never externalising that because it becomes an expectation and a commitment.

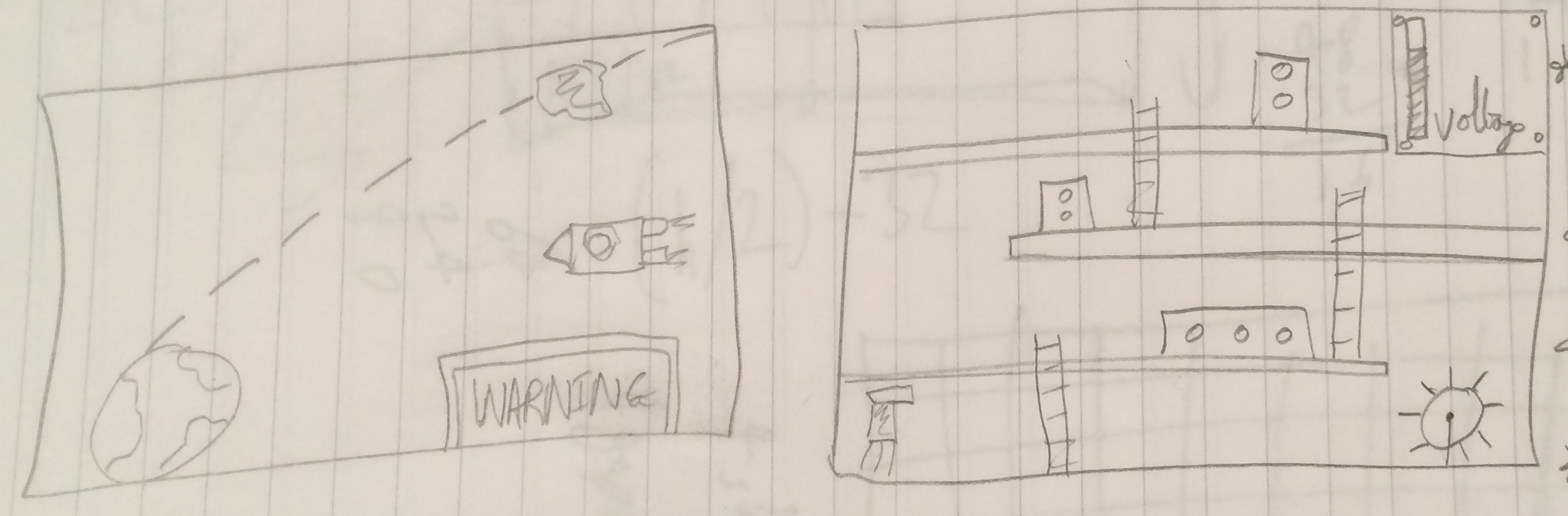

All my weaknesses as a software engineer aside, I made the fundamental error of dreaming up a cool game that was not within my reach of a 48 hour deadline. This is a completely avoidable self-imposed problem. The solution seems to be, sketch out the game in its entirety - all the objects in the game, all the components and all the behaviour. Make sure you have all the artwork at least approximated (I did this in Paper on the iPad because I could doddle on that while watching TV and it didn’t even feel like work). At this point you can identify elements that can be left out - think “what could I postpone if I was forced to launch this in an hour?” - or some other mind trick to force yourself to be ruthless with the scope of your game. One advantage of sketching everything on paper or in Paper on an iPad is that if time gets really tight and you don’t have super great pixel artwork ready - just chop up/scan in/photograph the sketches and use them as your assets. There will be people playing your game who think the hand-drawn nature of the artwork was a stylistic choice you made from the beginning and you know you ran out of time.

Onwards

So now I have a Trello board that makes it embarrassingly clear how unrealistic my game was for a 48 hour competition - where do I go from here? I think the best answer to that is to carry on with it, attack each task in the list and then realise the game is done (that sounds obvious but it’s impossible to realise when you’re ready to ship something unless you define up-front what you actually want to ship).

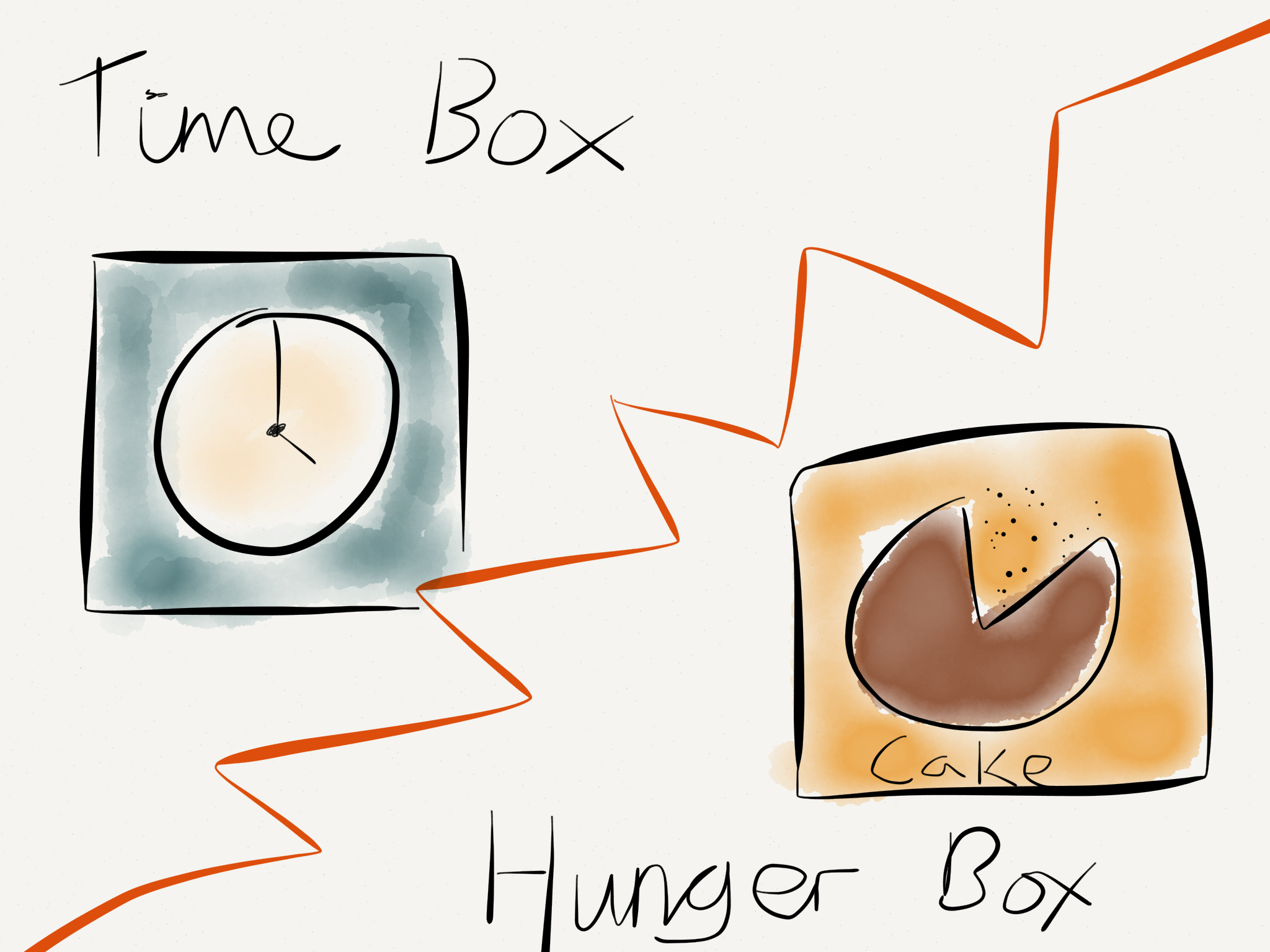

In Agile circles, we talk a bit about what it means to be Done. The “definition of done”, which can sound rather alien to somebody who’s not familiar with specifying that concretely. It’s essential to working progress otherwise you end up with tasks that linger on for days and weeks because they are quite simply never finished. Those aren’t tasks, they’re a waking nightmare. Sometimes there is no definition of done. This blog post doesn’t have a definition of done because I made an agreement with myself that I would write until I felt hungry then I would order some food. In Agile that’s usually called time-boxing and it usually isn’t hunger-based but might as well be. “Let’s time-box this for an hour” is a common phrase in Agile teams. It’s how you manage investigation tasks (otherwise they go on forever). We all need more, clearer definitions of done.

So Ludum Dare is over. I’m done with this blog post. I have plenty to practice and improve before next Ludum Dare and with any luck I’ll ship a game next time.